There’s a new term being tossed around in Korea lately: “쾌속세대”. It can be roughly translated “Generation High Speed” and is being used most directly to describe the Korean athletes who competed (and often won!) in the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. But, at least in the Jungang Daily, which I read, the term has quickly come to refer to the whole generation of Koreans born around the time of the 1988 Olympics in Seoul and who are now perceived as being the future driving force behind Korea’s emergence as a world beater.

What Korea-phile wouldn’t be heartened at this Korean pride in the newest generation to come of age? It’s great stuff… But lately, having read the book Ethnic Nationalism in Korea by Gi-Wook Shin (I reviewed it recently here.), I have also become more sensitive to the nationalism in Korean popular culture and an article on the front page of today’s Korean version of the Jungang Daily caught my eye.

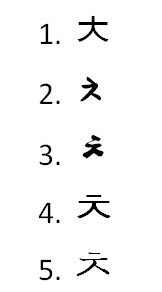

The article is entitled “아우내 장터의 망국세대, 밴쿠버의 쾌속세데, 대한분국 100년의 드라마 [EXPIRED LINK REMOVED: https://article.joins.com/article/article.asp?total_id=4038349]” (“The Republic of Korea’s 100-Year Drama: From the Generation of Aunae Market that Lost the Country to Generation High Speed in Vancouver”). To understand the full meaning here will require some additional historical background.

Today, March 1, is Korean Independence Movement Day (or, a more direct translation of the Korean: “March 1 Holiday”), which commemorates the failed declaration of independence by Korean patriots against the Japanese in 1919. The year 2010 marks the 100th anniversary of Japan’s formal colonization of Korea, an event of national humiliation which Koreans refer to as having “lost the country”. Aunae Market is a place near the city of Cheonan where an 18-year old rebel named Yu Gwan-sun led a demonstration in 1919, was arrested by the Japanese and died the next year in prison.

Today, March 1, is Korean Independence Movement Day (or, a more direct translation of the Korean: “March 1 Holiday”), which commemorates the failed declaration of independence by Korean patriots against the Japanese in 1919. The year 2010 marks the 100th anniversary of Japan’s formal colonization of Korea, an event of national humiliation which Koreans refer to as having “lost the country”. Aunae Market is a place near the city of Cheonan where an 18-year old rebel named Yu Gwan-sun led a demonstration in 1919, was arrested by the Japanese and died the next year in prison.

Eo-Ryeong Lee, a top editorial advisor at the Jungang Daily, writes today’s cover article in the form of a message addressed directly to the Generation High Speed athletes who competed in the Vancouver Olympics. He waxes glorious about how the Koreans of Generation High Speed have brought pride to the country by winning so many events which had previously been dominated by Western athletes. He even says that if Yu Gwan-sun has been born in 1988, she’d have been Yun-ah Kim, the Korean figure-skater who earned gold in women’s figureskating. And if Yun-ah Kim had been born in 1901, she’d be remembered as leading the demonstration at Aunae Market. Mr. Lee refers to all of them as national heroes. The implication here, of course, is that the Olympics are vicarious war and that winning gold medals brings a fitting conclusion to the process of restoring national pride which was lost 100 years ago.

Westerners reading this may think I’m going too far, but the truth of of the observation can really only be grasped by those who’ve stood amongst Koreans as they watch their athletes compete. From the World Cup to the Olympics, every Korean victory brings a little more healing to the national humiliation of 1910.

Westerners reading this may think I’m going too far, but the truth of of the observation can really only be grasped by those who’ve stood amongst Koreans as they watch their athletes compete. From the World Cup to the Olympics, every Korean victory brings a little more healing to the national humiliation of 1910.

And it’s not just in sports. How many Americans get warm fuzzies thinking about how many McDonald’s restaurants have been opened around the world? Do we want to sing the national anthem when Starbucks, Dell and Intel dominate foreign markets? On the other hand, every time Korean companies succeed overseas, Koreans are filled with happiness and pride.

Understanding this reality goes a long way toward making sense of Korean nationalism. As you see Koreans studying in universities, working in companies and competing in sports around the world, remember that they are “Generation High Speed”, sent by the nation to reclaim the national honor.

—————–

I might also point out one more interesting aspect. The Jungang Daily generally translates the main stories from the Korean paper to the English online version. But this one wasn’t translated, even though it’s on the front page! What could be the reason? Is it that Koreans don’t want to reveal this side of themselves? I don’t think so… I bet it’s that they don’t think non-Koreans would really find this interesting.

But it’s in understanding such aspects of Korean culture and history that we gain insights into what motivates Koreans and to find ways to work with Koreans in business and life effectively.